What happens when the clichéd “novel left in a drawer” is exhumed and exposed to light?

I’m finding out and sharing the results as I retype the manuscript of my 1970’s novel Exile in serial form, posting chapters as soon as I retype them. The third chapter follows, but click here if you need to catch up from the beginning.

3

Breakfast, like many European breakfasts, was a little thin. A small cup of coffee and a couple of croissants at a café is nothing, even if you’re only accustomed to a bowl or two of corn flakes and a couple of cups of American coffee. Robin was used to waiting until noon before eating, but John needed a lot to satisfy his 190 pounds of muscle. He tried asking for eggs in broken French which just left the waiter wondering if he was German or English. The waiter tried speaking a little German, but that didn’t help to convey any messages. John read the well-meaning confusion in the waiter’s eyes and left, empty, but glad about the contact he had made with another person. They had both felt compassion for the other’s confusion.

It took a while longer to get to the train station. Robin only seemed impressed by one thing along the way, a Communist party headquarters covered with red banners and posters.

“That’s great,” Robin stated, pointing toward the flag covered building.

“What? To be a Communist?”

“No, but the French are tolerant enough to allow Communism function as a part of their political system. In the U.S., what do we have but two capitalist parties? The French are more politically open-minded.”

“Do you believe that?”

“What?”

“What you just said. That there’s a big difference between parties. I don’t care whether they’re Republican or Communist…Can’t you see that they’re all the same?”

“Why?” Robin seemed surprised by John’s responses. He simply assumed that anyone who looked and dressed like John had to have leftist leanings, even if he was only a liberal Democrat.

“Because they all accept a basic view of society that I rejected a while ago, that people have to be controlled and that they aren’t capable of living on their own. I mean even your most ‘liberal’ governments are repressive. They put your mind in chains with their schools and TV, and when there’s one tool left to destroy their vision of reality, hallucinating – entering other forms of reality – they outlaw that. Fuck! I’m not even allowed to kill myself as a means of escape.”

Speechlessness overtook Robin. He had never heard these concepts expressed without a veneer of academic verbal fog obscuring the real emotions at their base. He always found these concepts of “other realities” very hard to accept anyway. After all, this world is so tangible. Every physical object can be touched and examined until one reaches the point of collapse and the object still doesn’t disappear or change appreciably. He knew that his mind was full of abstract ideas from his fifteen years of schooling and he could see, theoretically, how these ideas could be attacked. However, the thought never entered his mind that the common sense view of reality – reality – itself was little more than an abstract idea.

By this time, their conversation was cut short naturally as they found themselves in the Gare du Nord. All of a sudden, they were surrounded by people just like themselves. Everywhere they looked there were more people in their early twenties out to discover the world with their backpacks and railpasses. This scene was growing a little comical for Robin. He had been travelling with his friend for two months by train, and now every train station in every country in Europe looked the same, with the same percentage of natives, the same percentage of beautiful girls and women, the same porters, the same percentage of Canadian flags. There’s something that impressed Robin, the way in which the young Canadians distinguished themselves from the Americans by plastering their backpacks and sleeping bags with giant red maple leaves. He was going to mention this to John until he pictured John’s reply.

(“What makes their nationalism any better than anyone else’s?”)

Those might not have been the exact words he would’ve used, but he would definitely question nationalism in general and Robin would be left speechless. “Of course I don’t like any nationalism,” would be the beginning of his response; he would then find himself defending his contradictions.

Here he was, the bright, young intellectual who could answer his professors’ queries without thinking, but his ideas were being trampled by a wild-eyed drop-out who he had only met a couple of hours earlier. It was easy for him to argue with professors, because he had already accepted their world view. They accepted his arguments as valid as long as he didn’t stray beyond this view.

But now – now he had finally met someone who wouldn’t accept the framework of his arguments at all, someone who didn’t even accept “frameworks” as a basic concept, and he was lost – totally.

Whenever an intellectual problem like this confronted Robin, he took the same course. He ran away from it. He had to find some other chore to keep his mind busy, so he suggested to John that they make the train reservation and get that out of the way. He had been in this station on a few occasions during the summer, because this was where the trains headed for Scandinavia and Holland departed from. He knew exactly where to turn left and where to turn right to get to the ticket windows and reservation office.

“I’ll try my French this time to see if we have more luck than we did back in that café,” Robin said as they got in line. By trying to form French sentences in his mind, he quickly forgot the problems which had been bothering him only moments before.

“Monsieur?”

The woman behind the desk startled Robin. He hadn’t been aware of his place in the line.

“Ah…Oui,…je voudrais faire les reservations à Genève,” Robin attempted to pronounce.

“Do you speak English?”

This was always the question that he heard when he started in with his one year of college French. It annoyed him a little that he was never given a chance to speak French. After all, he would only get better with practice. In English, it only took him a few minutes to convert John’s hundred francs into a ticket and reservation to Geneva.

“What are you going to do today?” Robin asked. He was hoping that they could do something together, because he already knew Paris pretty well (he thought) and he knew that he’d get bored quickly if he just walked the streets by himself.

“What’s interesting? I’ve never been in Paris before.”

Good, this was his opportunity. “The whole area around the Champs-Élysées is good. There’s usually something going on in les Tuileries and we can grab lunch around there. Maybe see the Eiffel Tower? We can’t do too much considering you’re only going to be here for one day.”

Robin had already latched himself onto this new friend fairly securely. It was a mistake he commonly made with anyone who interested him, and John probably would have resisted had their relationship continued any longer.

Right now, John was enjoying the company. He was glad to meet someone on his first day in Europe. It was someone he could communicate with too, even if his mind was a little closed. Besides, he brought back those memories of the mountains. He might as well stay with him during the day and travel with him at least as far as Geneva. He couldn’t see staying with Rob’s friend though if he could catch a night train to Stalden and the Alps.

They had been standing in silence for thirty seconds or so. It wasn’t an awkward silence. They were both engrossed in their thoughts.

“So, what do you think we should do?” Robin finally began.

“Going to see the sights sounds okay to me. Do you have an extra subway ticket?”

“Yeah, don’t worry about it,” and they were on their way.

After surfacing near the Arc de Triomphe, they decided to just stroll down the Champs-Élysées. John was asking questions about the other cities that Rob had visited. He seemed interested in the Scandinavian cities.

Robin explained at length how much friendlier he found everyone in the Scandinavian cities and how beautiful the countryside was. John listened, but his attention lapsed quickly. Beside the fact that his mind was becoming entangled in the masses of passing faces, he had heard all this talk of friendly Scandinavians before. As for the countryside, he had already hitched and camped in Europe and he hadn’t seen anything that came close to the Alps just for the sheet dizziness caused by their beauty.

Thinking of dizziness, he hadn’t had anything to eat since the croissants of breakfast and his hunger was starting to get to him. Besides, they were passing a McDonald’s now. John didn’t share much of Robin’s respect for French cuisine. He was more than satisfied by a hamburger, fries, and something to drink. Entering a restaurant run by an American company can be a little mind-boggling when you’ve been out of the country for a couple of months. That’s what Robin was thinking when they didn’t even give him a chance to practice his French. They just saw him coming and asked for his order in English. The European McDonalds do have one large advantage over the domestic version. They serve good beer and they serve it cheap. “Sure beats a large Coke or strawberry shake,” John quipped.

Rob only had one beer. John drank about four – enough to get a little buzzed anyway. He started talking to a windburnt balding man with a cowboy hat and a string tie who looked as typical of the American Midwest as they come.

“Howdy,” John began cheerfully. He always seemed to change his personality to fit the person. All of a sudden, he was 200 pounds of young truck driver or construction worker. “How d’ya like Paris?”

The cowboy replied a little hesitantly at first. “The monuments are impressive, but it doesn’t have anything over Washington, D.C.”

“You’re from the East Coast?” John went on. He knew that anyone started to open up (positively or negatively) if you talked about their home.

“No, not even close. I live down in Kansas. Um, wheat farmin’. But I do fairly well and the misses here likes to take a trip every year. The kid’s old enough to take care of the place so that’s why I’m here and that’s why I know Washington, D.C. so well. See America first, y’know.” More from courtesy than curiosity, he asked, “Where you from son?”

“California. I work down in LA.”

“Oh, you don’t go to school?” he asked, a little surprised, as he twiddled a twenty centime piece between his thumb and forefinger and took a sip from his Coke.

“No, I decided that school wasn’t for me so I went to work in a factory after a couple years of college.”

Their conversation continued for what seemed like hours to Robin. After all, what could he find interesting in this old wheat farmer? All they talked about was the weather and the differences between farming in the Midwest and on the West Coast. John’s knowledge of soil differences and farm automation began to amaze Robin until John mentioned that he was brought up on a California sugar beet farm. (He only found out later that that had been a lie engineered to keep the conversation moving.)

After they seemed to have exhausted their common farm knowledge, they began talking about Paris itself.

“What do you think of the Arc de Triomphe?”

“It’s impressive. It’d be nice if we had a monument like that in honor of our wars. I was really impressed by the Eiffel Tower too. Y’know that must’ve been some engineerin’ feat for its day.”

As the cowboy was saying this, he didn’t notice the life flowing into John’s eyes.

“Yeah, but have you ever seen it dance?”

“huh?” Up until now everything they were talking about made sense to him. Everything was familiar to him and new he was confused.

“But don’t you know that when you’re tripping anything can dance. I’ve seen the Eiffel Tower dosey-do with the Arc many a time.”

John’s friend with the cowboy hat actually seemed afraid as he made excuses for his hasty retreat. He murmured something about a bus waiting for him as he grabbed his hat and wife and left.

“Why did you do that?” Robin asked, definitely showing some annoyance.

“Do what?”

“Why did you have to disturb that guy like that and why’d you have to lie to him? You’ve never even seen the Eiffel Tower, let alone seen it dance!”

“Obviously he’s not the only person I disturbed.” John’s constantly calm way of talking was only annoying Robin more. He could only enjoy an argument where both parties began to lose control.

“I’m only disturbed because what you did was senseless.”

“No, that’s where your wrong. It wasn’t senseless. I had to teach both of you a lesson.”

“Both of us?” incredulously.

“Yeah, now listen. With him it was obvious. You saw how he was standing at that counter. He was so smug it was ridiculous. He was feeling superior to all his friends and family because none of his friends and family had the money to take the trips that he took. At the same time, he was feeling superior to all these French people and their rough toilet paper, cheap beer, and nasal language. Besides, he was a veteran. He helped liberate these people from Hitler and they don’t even show their gratitude. When someone is that smug about himself, his faith in his view of reality is at its height. I just…”

“I didn’t hear him say any of those things about himself.” Robin was glad. His friend was finally ready to talk at length – finally ready to argue.

“He didn’t have to tell me his life story. I could see his self-assuredness a mile away. The details aren’t that important. I just challenged his world view a little bit. He lost a little self-confidence, but he lost a little stupidity along with it. He was…”

“You said that you were teaching me a lesson too. What was that?”

“Shit, you’re impatient. The thing I wanted to show you is harder because you’re even more sure of your ideas. In a lot of ways you think the same as that pot-bellied cowboy or the people who pass drug laws.”

“Ah, now come…” John had gone too far now. (I’m Robin Jackson. I fight for civil liberties and I don’t care what drugs you take.)

“No. Now you come on. I think I know what you’re thinking and your liberal leanings don’t amount to a pile of shit with me. You share your view of this world with a Kansas wheat farmer and a narc. You may even be able to explain chemically why I can see a building come to life with LSD, but you don’t believe that it can. You don’t believe that there’s a world where buildings dance and people are frozen. But I do. I’ve seen that world, and if I can’t believe my senses what can I believe?”

Robin was speechless. His friend was crazy. Here he was speaking at full voice in a room full of Americans (a room full of staring Americans, he had convinced himself by now. He was too scared to turn around and look). Robin suggested that they leave the restaurant and they both walked out. Robin was still sure that there were at least ten pairs of trailing eyes following them through the door. On the way out they passed a record shop with the new Dylan album in the window. Robin hadn’t seen it before, but John had heard most of it right before his departure. The album and related topics were the focus of their conversation as they continued down the Champs-Élysées.

“Such a great lyricist…”

“Yeah, especially in Blonde on Blonde.”

“Fuck! Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands, that song tears me apart every time I hear it.” ….

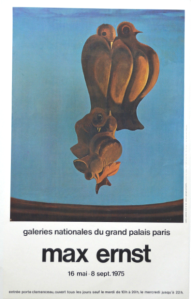

Superficial things like this – having similar musical tastes – convinced Robin that he and John were alike down deep. He thought that their friendship was cemented even faster when they passed the Grand Palais where a large Max Ernst exhibition was taking place. Rob had been to the exhibition about a month before and he talked at length about how much he liked it. John spent most of the walk nodding in agreement and saying, “Yeah, he’s one of my favorite artists too.”

Robin liked to consider himself an intellectual, but he never looked much deeper than these surface comments. If he had asked himself why they liked the same things, he would have been struck by the differences between them. Robin liked Ernst for a few reasons. He liked his use of color and he thought he was funny. He told everyone how much he liked Ernst’s “Dejeuner sur l’herbe” where the plants were eating the nude woman. He thought it was the perfect parody of Manet’s painting of the same name where two men and a nude woman were eating lunch on a lawn. He had another reason for liking Max Ernst, even though he only partially admitted it to himself. That was because Anne said she liked him (“Be sure to see that show,” she told him as he departed in June). She accounted for part of his resurgence of enthusiasm for Dylan too. His tastes in music and art always went through subtle changes when he found himself in the shadow of a new girl.

John could see some of these things in his companion and he simply laughed them off. He like Max Ernst for the same reason he liked Dali or any other surrealist. He understood their paintings implicitly for a very simple reason. He saw his own mind as surreal.

Back in 2017

Even though in don’t think the year will be mentioned anywhere in this manuscript, anyone with an internet connection can find out easily that the Max Ernst retrospective at the Grand Palais took place between May and September of 1975. The poster at the beginning of this post featuring Ernst’s “Monument aux oiseaux” is the same as one I carried back from Paris and had on various dorm and bedroom walls for years (my poster is now lost, but it lives forever on the web). And if it’s 1975, the new Dylan album mentioned by John and Robin was therefore, of course, Blood on the Tracks.

Chapter Four has now been retyped and posted here (8/30/2017).